.jpg)

Distributed System - Replication(Leader Less Replication)

Distributed Systems Replication Leaderless Replication

This is a skimmed version of Chapter 5 ‘Replication’ from the book design_data_intensive_applications. I would recommend you to first read the whole chapter and use these notes for revision purpose only.

LEADER LESS REPLICATION

- Some data storage systems allows any replica to directly accept writes from clients.

Examples

- Amazon used it for its in-house Dynamo system

- Riak, Cassandra, and Voldemort are open source datastores with leaderless replication models inspired by Dynamo, so this kind of database is also known as Dynamo-style.

How it works

- In some leaderless implementations, the client directly sends its writes to several replicas, while in others, a coordinator node does this on behalf of the client.

- However, unlike a leader database, that coordinator does not enforce a particular ordering of writes.

WRITING TO THE DATABASE WHEN A NODE IS DOWN

- In a leaderless configuration, failover does not exist.

- Figure shows what happens: the client (user 1234) sends the write to all three replicas in parallel, and the two available replicas accept the write but the unavailable replica misses it.

- Let’s say that it’s sufficient for two out of three replicas to acknowledge the write: after user 1234 has received two ok responses, we consider the write to be successful.

- The client simply ignores the fact that one of the replicas missed the write.

What happen when unavailable replica comes back online?

- Any writes that happened while the node was down are missing from that node. Thus, if you read from that node, you may get stale (outdated) values as responses.

- To solve that problem, when a client reads from the database, it doesn’t just send its request to one replica: read requests are also sent to several nodes in parallel.

- The client may get different responses from different nodes; i.e., the up-to-date value from one node and a stale value from another.

HOW TO HANDLE CONSISTENCY OF DATA IN ALL REPLICAS?

- The replication scheme should ensure that eventually all the data is copied to every replica.

- Two mechanisms are often used in Dynamo-style datastores

Read Repair

- When a client makes a read from several nodes in parallel, it can detect any stale responses.

- For example, in Figure, user 2345 gets a version 6 value from replica 3 and a version 7 value from replicas 1 and 2.

- The client sees that replica 3 has a stale value and writes the newer value back to that replica.

- This approach works well for values that are frequently read.

Anti-entropy process

- In addition, some datastores have a background process that constantly looks for differences in the data between replicas and copies any missing data from one replica to another.

- Unlike the replication log in leader-based replication, this anti-entropy process does not copy writes in any particular order, and there may be a significant delay before data is copied.

HOW THE WRITE IS CONSIDERED SUCCESSFULL?

You can read about this in detail here: Quorums for reading and writing

Detecting Concurrent Writes

- The situation is similar to multi-leader although in Dynamo-style databases conflicts can also arise during read repair or hinted handoff.

- The problem is that events may arrive in a different order at different nodes, due to variable network delays and partial failures.

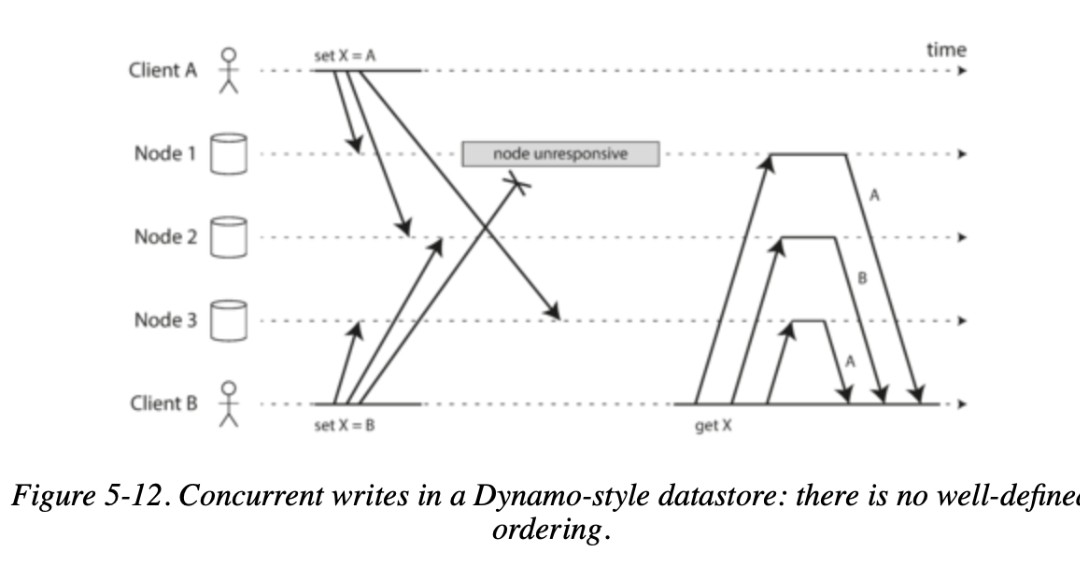

- For example, Figure 5-12 shows two clients,

- A and B, simultaneously writing to a key X in a three-node datastore:

- Node 1 receives the write from A, but never receives the write from B due to a transient outage.

- Node 2 first receives the write from A, then the write from B.

- Node 3 first receives the write from B, then the write from A.

- If each node simply overwrote the value for a key whenever it received a write request from a client, the nodes would become permanently inconsistent, as shown by the final get request in node 2 thinks that the final value of X is B, whereas the other nodes think that the value is A.

We briefly touched on some techniques for conflict resolution in Handling Write Conflicts

Concurrency, Time, and Relativity

- It may seem that two operations should be called concurrent if they occur “at the same time”—but in fact, it is not important whether they literally overlap in time.

- Because of problems with clocks in distributed systems, it is actually quite difficult to tell whether two things happened at exactly the same time.

- For defining concurrency, exact time doesn’t matter: we simply call two operations concurrent if they are both unaware of each other, regardless of the physical time at which they occurred.

Last write wins (discarding concurrent writes)

- One approach for achieving eventual convergence is to declare that each replica need only store the most “recent” value and allow “older” values to be overwritten and discarded.

- Even though the writes don’t have a natural ordering, we can force an arbitrary order on them.

- For example, we can attach a timestamp to each write, pick the biggest timestamp as the most “recent,” and discard any writes with an earlier timestamp.

- This conflict resolution algorithm, called last write wins (LWW), is the only supported conflict resolution method in Cassandra and an optional feature in Riak.

Cons of LWW

- LWW achieves the goal of eventual convergence, but at the cost of durability: if there are several concurrent writes to the same key, even if they were all reported as successful to the client because they were written to w nodes, some of those writes may be lost.

- There are some situations, such as caching, in which lost writes are perhaps acceptable. If losing data is not acceptable, LWW is a poor choice for conflict resolution.

The “happens-before” relationship and concurrency

- “How do we decide whether two operations are concurrent or not?

- An operation A happens before another operation B if B knows about A, or depends on A, or builds upon A in some way. Whether one operation happens before another operation is the key to defining what concurrency means.

- In fact, we can simply say that two operations are concurrent if neither happens before the other (i.e., neither knows about the other)

- Thus, whenever you have two operations A and B, there are three possibilities:

- either A happened before B,

- or B happened before A,

- or A and B are concurrent.

- What we need is an algorithm to tell us whether two operations are concurrent or not. If the operations are concurrent, we have a conflict that needs to be resolved.

Capturing the happens-before relationship

To keep things simple, let’s start with a database that has only one replica. Once we have worked out how to do this on a single replica, we can generalize the approach to a leaderless database with multiple replicas.

-

Let’s look at an algorithm that determines whether two operations are concurrent, or whether one happened before another.

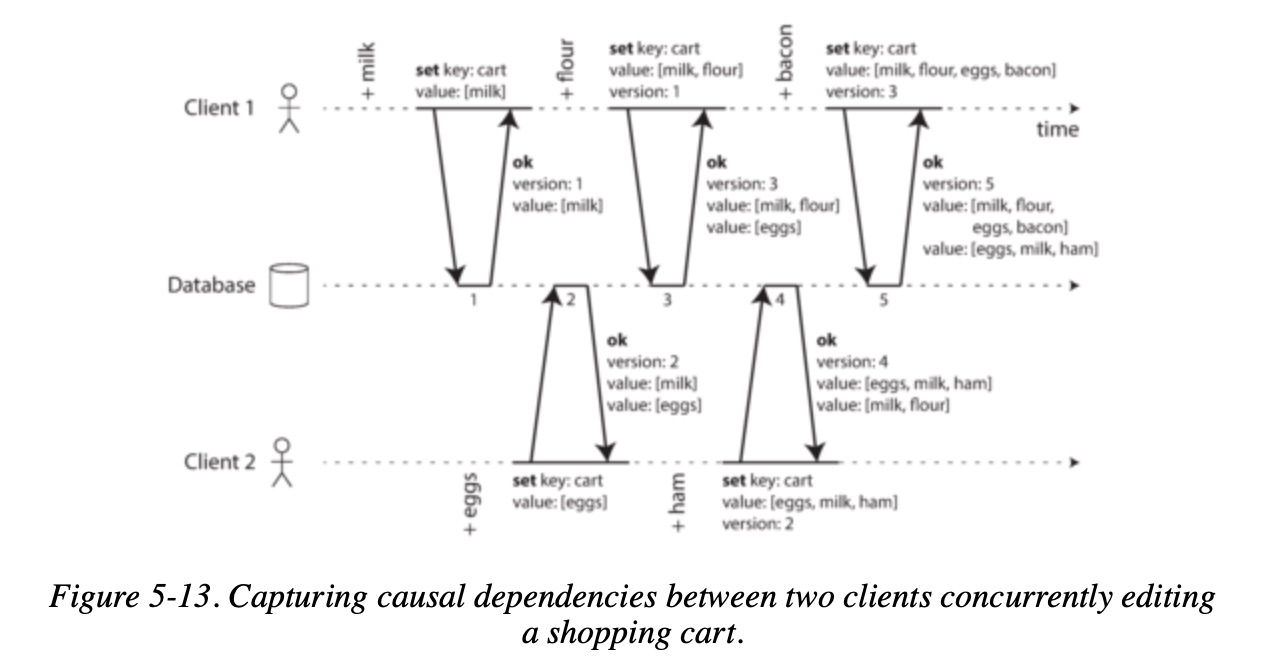

- Client 1 adds milk to the cart. This is the first write to that key, so the server successfully stores it and assigns it version 1. The server also echoes the value back to the client, along with the version number.

- Client 2 adds eggs to the cart, not knowing that client 1 concurrently added milk (client 2 thought that its eggs were the only item in the cart). The server assigns version 2 to this write, and stores eggs and milk as two separate values. It then returns both values to the client, along with the version number of 2.

- Client 1, oblivious to client 2’s write, wants to add flour to the cart, so it thinks the current cart contents should be [milk, flour]. It sends this value to the server, along with the version number 1 that the server gave client 1 previously. The server can tell from the version number that the write of [milk, flour] supersedes the prior value of [milk] but that it is concurrent with [eggs]. Thus, the server assigns version 3 to [milk, flour], overwrites the version 1 value [milk], but keeps the version 2 value [eggs] and returns both remaining values to the client.

- Meanwhile, client 2 wants to add ham to the cart, unaware that client 1 just added flour. Client 2 received the two values [milk] and [eggs] from the server in the last response, so the client now merges those values and adds ham to form a new value, [eggs, milk, ham]. It sends that value to the server, along with the previous version number 2. The server detects that version 2 overwrites [eggs] but is concurrent with [milk, flour], so the two remaining values are [milk, flour] with version 3, and [eggs, milk, ham] with version 4.

- Finally, client 1 wants to add bacon. It previously received [milk, flour] and [eggs] from the server at version 3, so it merges those, adds bacon, and sends the final value [milk, flour, eggs, bacon] to the server, along with the version number 3. This overwrites [milk, flour] (note that [eggs] was already overwritten in the last step) but is concurrent with [eggs, milk, ham], so the server keeps those two concurrent values.

-

Note that the server can determine whether two operations are concurrent by looking at the version numbers—it does not need to interpret the value itself (so the value could be any data structure).

-

The algorithm works as follows:

- The server maintains a version number for every key, increments the version number every time that key is written, and stores the new version number along with the value written.

- When a client reads a key, the server returns all values that have not been overwritten, as well as the latest version number. A client must read a key before writing.

- When a client writes a key, it must include the version number from the prior read, and it must merge together all values that it received in the prior read. (The response from a write request can be like a read, returning all current values, which allows us to chain several writes like in the shopping cart example.)

- When the server receives a write with a particular version number, it can overwrite all values with that version number or below (since it knows that they have been merged into the new value), but it must keep all values with a higher version number (because those values are concurrent with the incoming write).